Extract from the Late Beating Up

His Highness was now making halt in Chalgrove cornfield: about a mile & half short of Chiselhampton Bridge. Just at this time (being now about 9 a clock) we discerned several great Bodies of the Rebels Horse and Dragooners, coming down Golder-hill towards us; from Esington and Tame: who (together with those that had before skirmished with our Rear) drew down to the bottom of a great Close, or Pasture: ordering themselves there among trees beyond a great hedge, which parted that Close from our Field. My Lord of Essex’s Relation, here mentions Captain Sanders Troop, and Captain Buller with 50 commanded men; Captain Dundasses Troop of Dragooners, with some few of Colonel Melves. But surely these were not all their Forces.

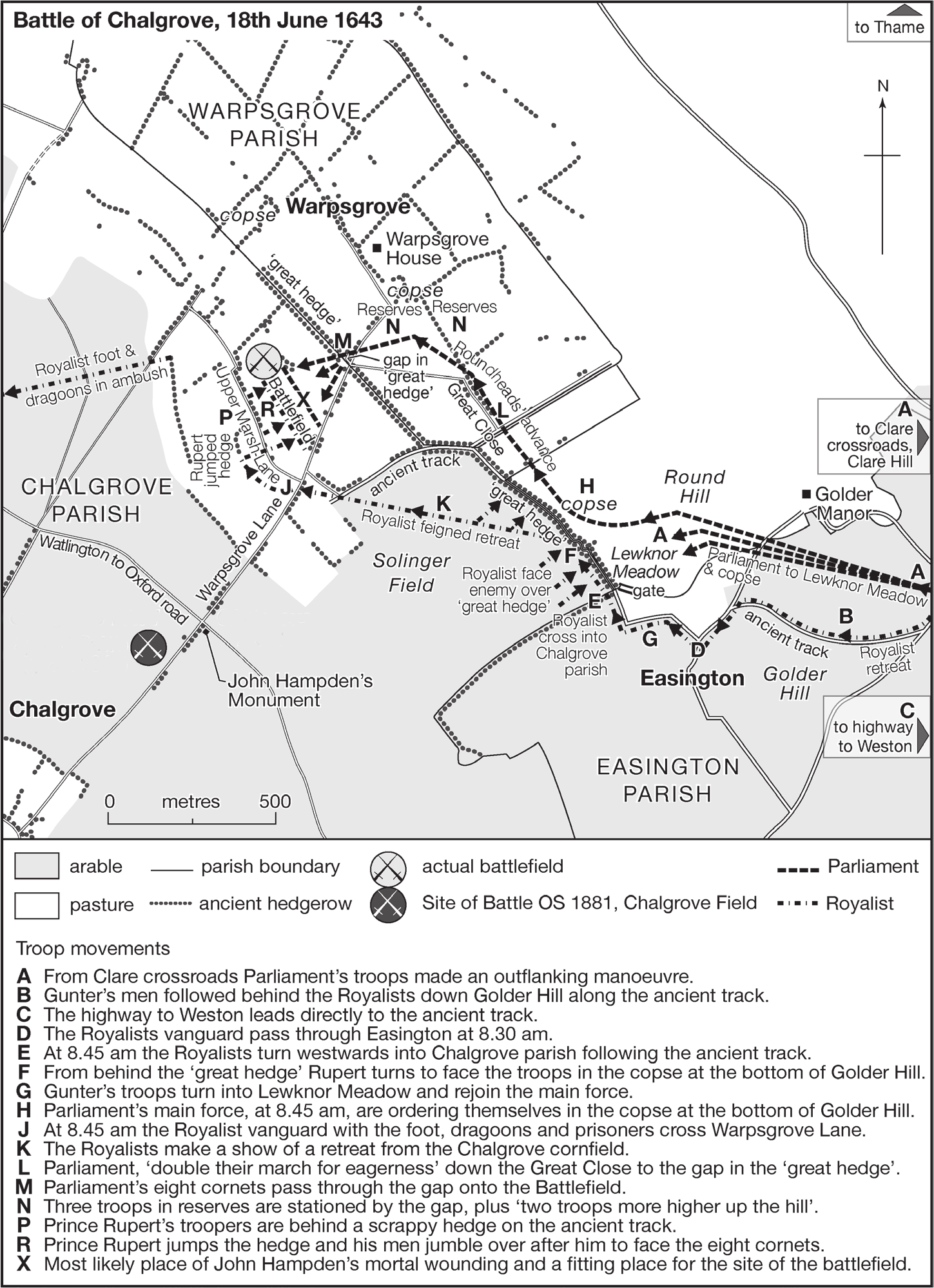

The Royalist vanguard was already entering Chalgrove so honour and principle among the senior officers who had come into the fight had to be discarded. (A) Hurriedly Gunter made a plan of action. (B) Gunter, Crosse and Sheffield’s troops were to harass the Royalists’ rear while the others were to do an outflanking manoeuvre as the Royalists turned westward towards Chiselhampton. It is to be noted that all the participants who were involved with the Battle have been followed step by step, in a logical manner, to arrive at the Chalgrove cornfield, or coming down Golder Hill, at around 08.45. Every troop movement to get the protagonists facing each over a great hedge is accounted for in a time frame so that each individual or troops’ whereabouts concur. The skirmish involving 300 Parliamentarians occurred before Chalgrove and before John Hampden was still to be wounded in battle. Sir Philip Stapleton, who was waiting in Thame for intelligence, received Dundasse’s detachment after 09.30 so arrived too late to save the situation at Chalgrove. The routing Parliamentarian troopers, fleeing for their lives over Golder Hill after the Battle, met with Stapleton beyond the hill a little after 10.00, which marked the end of the Battle.

(D) The rear of the Royalist’s vanguard with the foot troops and prisoners had passed through Easington following the ancient track that had brought them from South Weston and down Golder Hill. (E). The head of the vanguard turned westwards leading the foot and dragoons through the great hedge out of Easington parish into Solinger field, the Chalgrove cornfield. The Prince of Wales’ Regiment led the cavalry into Solinger field followed by the Prince’s own Regiment with the Prince’s Lifeguards to the rear. General Percy’s Regiment brought up the rear of the column of troopers. ‘His Highness was now making halt in Chalgrove cornfield’, Bernhard de Gomme the narrator stated. His description of the terrain and reference to the Rebel troops coming down Golder Hill from Easington and Thame and the cavalry’s order of march gives the precise spot where the Prince was standing when he made halt in the Chalgrove cornfield. (F). The Prince ordered the cavalry to turn from column into line. This manoeuvre brought the Royalist’s troopers into battle formation facing towards Golder Hill. Gomme remarked they came from Easington, which from his viewpoint in the Chalgrove cornfield is obliquely on the right hand and marked Parliament’s left flank. Thame is six miles directly ahead of the Prince in a northerly direction and this statement marks the limit of Parliament’s right flank. From this statement it is deduced Parliament’s troopers are spread out over a 500 yard frontage storming down Golder Hill as a disorderly rabble. Gomme identified and highlighted ‘those that had before skirmished with our Rear’ from the ‘several great Bodies of the Rebels Horse and Dragooners’. Any lingering doubts that Chalgrove was a skirmish are extinguished by Gomme’s statement.

(H) Parliament’s outflanking manoeuvre is promptly halted on observing the Royalist’s cavalry high above them in Solinger field and an impenetrable great hedge in front of them. A great hedge is a double line of stock proof hedges with a ditch between that marks a parish’s boundary. Ways through a great hedge are limited and from Lewknor Meadow where the Parliament’s troops are being ordered into Cornets of 70 men Warpsgrove Lane by Warpsgrove House is the closest. A Cornet of men is a company troop that is led by a Captain with a few Lieutenants to convey his orders. The Ensign carries the company’s Standard and leads the Cornet.

(J) The Royalists’ vanguard was nearly a mile ahead of their cavalry, well on the way to Chiselhampton Bridge. The dragoons with them were able to execute a rolling retreat by lining the hedges and waiting in ambush. Parliament’s troops wanted to free the prisoners and regain some credibility for Essex, but Rupert had set a trap. The great hedge was a formidable and continuous barrier with few gaps. The lane from Chalgrove up to Warpsgrove House was one such gap and was 1,000 yards from where they faced Rupert. The rear of the infantry column had crossed Warpsgrove Lane by 08.45 and was effectively out of danger. If Parliament’s men tried to attack the infantry they would first have to gallop 1,000 yards to the gap, squeeze through it into Warpsgrove Lane and chase through the lanes in pursuit only to find the ambush set by the dragoons. This action would have left over 1,000 of the finest Royalist troopers at their rear to press them further into the ambush and absolute annihilation. The question for Gunter, in the frustration of ordering his army, was how he could attack without risking everything. Gunter was aware that reinforcements would be coming from Thame and maybe hoped that Stapleton had sent a large detachment directly to Chiselhampton. Gunter’s only option was to delay the Royalist’s retreat, but before he could finalise his plans Rupert added to his predicament.

(K) Rupert ordered his troopers from line into column and calmly left the Chalgrove cornfield to follow in his infantry’s footsteps, his right flank covered by the great hedge. The ancient track bends away from the great hedge at the end of Solinger field to avoid marshy land. The Prince of Wales’ Regiment were the first to cross Warpsgrove Lane into Upper Marsh Lane, this being 400 yards south from where the lane passes through the great hedge. The Prince’s own Regiment, his Lifeguards and General Percy’s Regiment followed behind the Prince of Wales’ regiment and on turning from column into line this was the Royalist’s battle formation. Here they waited the trap was set the bait of the prisoners and booty tantalisingly retreating from view. Every minute of delay Parliament’s quarry were closer to Chiselhampton and safety.

(L) Gunter saw his quarry nonchalantly walking away. In panic he sorted Parliament’s men into thirteen troops and a Forlorn Hope of Horse. ‘The Rebels advanced cheerfully: doubling their march for eagerness’ to try and get ahead of the enemy. The great hedge bends away towards Warpsgrove House leaving an ever greater distance between the departing Royalists. Unable to get through the great hedge they galloped a 1,000 yards down the great Close towards Warpsgrove House where Warpsgrove lane passes through the great hedge.

Gunter’s troops reached Warpsgrove lane and the gap in the great hedge close to where Hitchcock’s Antique Centre is now located. He deployed five troops, approximately 350 men, as reserves. The Late Beating Up has :

‘Besides which, they had left a Reserve of three Cornets in the Close aforesaid among the trees by Wapsgrove House, and two Troops more higher up the hill, they were in sight of one another, by 9 a clock in the morning.’

Gunter deployed probably Sanders and Buller’s troops led by Colonel Dulbiere as a Forlorn hope of Horse and Dundasse’s dragoons. Col Dulbiere took his men down Warpsgrove lane towards Chalgrove to the hedge line where the Royalists’ were deployed. Gomme remarked:

‘and to the end of it (the hedge) came their Forlorn hope of horse’.

Captain Middleton led Colonel Mills’ dragoons to the centre of the hedge line and began firing at close range upon the Prince’s Lifeguard. Sergeant Major Gunter’s troop entered the field and took the centre. Captain James Sheffield had the right flank and Captain Richard Crosse, with Colonel John Hampden in its ranks were on Gunter’s left. The other five Cornets comprised of officers who had been collecting their regiments pay and had been sent by Essex to Chalgrove, were deployed as instructed.

Gomme described the scene and the Prince’s tactics and best told in his words:

‘We were now parted by a hedge, close to the midst whereof the Rebels brought on their Dragooners: and to the end of it came their Forlorn hope of horse. Their whole Body of 8 Cornets faced the Princes Regiment and Troop of Lifeguards, and made a Front so much too large for the Princes Regiment, that two Troops were faine to be drawn out of the Prince of Wales Regiment, to make our Front even with the enemy’.

Gomme’s description of the Royalist’s battle order is told in his own words.

‘The Princes battalions were thus ordered. His Highness’s own Regiment, with the Lifeguards on the right hand of it, had the middle-ward: the Prince of Wales his Regiment making the Left -wing, and Mr. Percy’s having the Right. Both these Regiments were at first intended for Reserves: though presently they engaged themselves in the encounter. It was diverse of the Commanders counsels, that the Prince should continue on the retreat, and so draw the Rebels into the Ambush, but his Highness’s judgement overswayed that; for that ( saith he ) the Rebels being so near us, may bring our Rear into confusion, before we can recover to our ambush. Yea ( saith he ) their insolency is not to be endured.

This said, His Highness facing all about, set spurs to His Horse, and first of all (in the very face of the Dragooners) leapt the hedge that parted us from the Rebels.’

It is clear that hedge that Rupert jumped is not the great hedge.

‘The Captain, and rest of His Troop of Lifeguards (everyman as they could) jumbled over after him: and as about 15 were gotten over, the Prince presently drew them up into a Front, till the rest could recover up to him. At this the Rebels Dragooners that lined the hedge, fled: having hurt and slain some of ours with their first volley’.

Gomme who was with Prince in the centre stated,

‘Some of ours affirm, how they over-heard Dulbiere (who brought up some of the Rebels first Horse ) upon sight of the Princes order and dividing of his Wings, to call out to his People to retreat, least they were hemmed in by us.’

Rupert called out two troops from the Prince of Wales’ regiment to make his front even with the enemy. Captains Martin and Gardiner of the Princes own Regiment led the first charge. They received a volley of pistol shot at a distance and another at close range. Swords drawn Prince Rupert charged with his Lifeguard and in the mêlée used their pistols to deadly effect. It is likely that John Hampden was mortally wounded in this first charge and in the confusion was able to leave the Battlefield.

The Parliamentarians were trapped. To the west was marshy ground and the waiting ambush. To the east was hard enclosures and the Royalists’ had command of the south. Gunter deployed about 600 men onto the battlefield most of whom were used to giving orders and objected on principle to obey the instructions of a lesser officer. Whereas the Royalists had over 1,000 elite troops The Prince Rupert’s Lifeguard handpicked from the most loyal and brave were probably selected from his own Regiment’s ranks. The great hedge to the north was impassable except for the gap where Warpsgrove lane passed through it. Shortly after the battle began but after John Hampden is wounded two troops out of General Percy’s regiment rode out and took the gap leaving Parliament’s reserves cut off from the battle. Maybe a horse or two bolted from the battlefield its rider or the horse wounded and found their way to Watlington, Colonel John Hampden’s field headquarters and the men are told their Colonel is badly wounded.

Gomme wrote,

‘Both these Regiments (Percy’s and Prince of Wales’) were at first intended for Reserves: though presently they engaged themselves in the encounter’.

Outnumbered near two to one Parliament’s troops were routed it was everyman for himself. Parliament’s men were trapped on the battlefield and unable to flee. The Royalists were able to reload their pistols and return to fray and fire at close range if they chose. Nine out of ten Parliamentarians’ were officers many being of a most senior rank. The ransom of such high ranking officers would fetch a high price or could be exchanged for men of rank being held by Essex. The choice was stark agree to be a true prisoner, a gentleman as a matter of principle would not break his word, or be shot. Parliament’s men were ‘wholly routed’ all fighting had ceased but as Colonel Dulbiere warned they were hemmed in unable to flee the battlefield.

The Prince had won the battle all fighting had stopped and three hundred men were standing among the litter of bodies of their fallen fellow officers. Through the gap on the other side of the great hedge 350 reserves still fresh and fully armed were blocked by General Percy’s men from coming to their comrade’s rescue. The Royalist’s had been in the saddle for twenty hours had fought over the last hour an exhausting battle and had expended their gunpowder. The horses were tired, hungry and thirsty as were the men on their backs. Parliament’s men fled the battlefield to their reserves and all were chased back over Golder Hill, stated Gomme. The gap in the great hedge was narrow and just wide enough for two maybe three horses to gallop through side by side. This part of the great hedge with the gap is still in the landscape. Having 300 horseman fleeing the battlefield in panic all trying to get through the gap in the great hedge at once would result in pandemonium. An order to form a column two abreast is easily executed and with Parliament’s officer’s agreement would be ready to storm through the gap at full gallop. The Royalist’s under their officer’s order chasing behind the ‘fleeing’ men brought confusion to the reserves. With cries of flee all is lost and outnumbered the reserves joined those racing over Golder Hill.

The Late Beating Up has:

‘The Rebels now flying to their Reserve of three Colours in the Close by Wapsgrove house, were pursued by ours in execution all the way thither: who now (as they could) there rallying, gave occasion to the defeat of those three Troops also. So that all now being in confusion, were pursued by ours a full mile and quarter (as the neighbours say) from the place of the first encounter. These all fled back again over Golder hill to Esington: and so far Sir Phillip Stapleton with his Regiment was not yet come.’

The Earl of Essex wrote a letter to the Speaker of the House of Commons 19th June 1643. On the 23rd June, The Commons House published a heavily censored letter purporting to be Essex’s letter. Gomme ridiculed the letter pointing out politely the lies. Essex’s letter has relating to Stapleton and after the skirmish in which Col John Hampden is alive and well has,

‘For when I heard that our men marched in the rear of the Enemy, I sent to Sir Phillip Stapleton, who presently Marched toward them with his Regiment; & though he came somewhat short of the Skirmish, yet seeing our men Retreat in disorder, he stopped them, caused them to draw into a Body with him, where they stood about an hour.’

Captain Dundasse reported to Gunter that reinforcement, the 750 officers sent by Essex from Thame, was on its way joined with the skirmishers. A detachment from Dundasse’s dragoons left Stokefield around 08.30 and with no sense of real urgency and on their old nags ambled into Thame after 09.30 to report to Stapleton. He received the message that Prince Rupert was leading 1,000 troopers and when they left was entering the parish of Chalgrove. Stapleton immediately brought the waiting troopers into order and led them with all speed towards Chalgrove. Six miles across country keeping the troopers together in their units and having left Thame after 09.30 Stapleton arrived at Chalgrove to see his fellow officers fleeing for their lives the time being after 10.00. A statement that records the battle of Chalgrove that began at Golder Hill 08.45 ended in Parliament’s utter defeat at around 10.15. Edward Hyde, later the Earl of Clarendon, wrote on the day they ‘engaged in a sharp encounter, the best, fiercest, and longest maintained that hath been by the horse during the war.’

‘They left us masters of the field, and leisure, by that, to survey the dead bodies’, wrote Gomme.

Riderless horses were rounded up for they were finest steeds dressed in tack of the highest quality. Tack from dead animals was stripped and loaded onto the fine steeds. Even those horses that were walking wounded provided they could limp back to Oxford were taken for the tack and if badly wounded made a meal for the troopers. Carts were pressed to take the spoils of war back to Oxford. After half an hour Prince Rupert left the battlefield and made his way to Chiselhampton Bridge. Hyde related:

‘and then his highness, with the new prisoners he had taken, retired orderly to the pass where his foot and former purchase expected him.’

Eighty chosen men agreed to be prisoners but many were injured and like Hampden were mortally wounded. The Mercurius Aulicus reported the next day:

‘he (Rupert’s men) slew above an hundred dead in the place’,

and in the circumstances this is a believable number. At around 14.00, at the head of his valiant men and displaying the spoils of war, Prince Rupert marched into Oxford to a triumphal hero’s welcome.

Back to Battle of Chalgrove 1643